|

Copyright © 2008 |

|

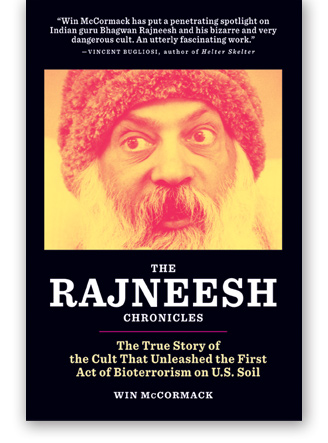

The Rajneesh Chronicles is a collection of in-depth investigative articles, originally published in Oregon Magazine, covering the time from the cult’s arrival in Oregon in 1981 to its dramatic disintegration at the end of 1985. This second edition of the definitive text on the Rajneesh cult includes an introductory chronology that extends the story up to the present time. While most press treated the cult’s antics as a humorous sideshow typified by the Bhagwan’s dozens of Rolls-Royces, Oregon Magazine's editor-in-chief Win McCormack and the magazine’s other writers systematically exposed the full range of the Rajneeshees’ depraved behavior, including their involvement in prostitution and international drug smuggling, sexual exploitation of children, attempted poisoning of local government officials and over 700 voters, abuse of the homeless, and the use of brainwashing techniques that bordered on torture. The tale of the Rajneesh has become an amorphous legend few inside or outside of Oregon actually understand. The Rajneesh Chronicles fully illuminates the shocking reality behind that legend. ISBN: 978-0-9825691-9-1 * $14.95 * Trade Paper Buy this book from Tin House Books for 20% off

An excerpt from The Biggest Criminal Conspiracy in the History of Oregon

In late June and early July 1981, people wearing bright orange or red clothing and long, beaded necklaces were spotted in the vicinity of Antelope, Oregon, a town of some forty people in the semiarid sagebrush reaches of central Oregon. They were, it was soon learned, disciples or followers of an East Indian guru, pictures of whose beaming, bearded countenance were displayed in lockets dangling from the ends of their necklaces, and they had just purchased the nearby, 64,000-acre Big Muddy Ranch straddling Wasco and Jefferson counties for $6 million. Their intention, spokespersons said, was to establish a “simple, agricultural commune.”

At the time of the Rajneesh group’s arrival, its background was almost completely unknown to most people in Oregon, as was that of its guru, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, who had arrived in the New York City area in early June on a medical visa and would soon join his followers at the ranch. Over the course of the next four and a half years, their activities in central Oregon would become major issues in the state and a near-obsessive preoccupation to many of its citizens. The central issue would be the legitimacy, under the state’s land-use laws, of the incorporation of the city of Rajneeshpuram, but intense controversy also would surround the group’s treatment of the citizens of Antelope, whose city council it came to control; the immigration status of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh and other foreigners living at Rancho Rajneesh; the accumulation of a large store of lethal weapons on the ranch; and the acerbic, bellicose personality of Ma Anand Sheela, the group’s chief spokesperson, who repeatedly heaped vituperation on Oregonians for their “bigotry.” (In Laguna Beach, California, Rajneesh representatives would wage another bitter but finally successful battle to wrest ownership of the Church of Religious Science of Laguna Beach from its original members.) At perhaps the height of the struggle between the Rajneeshees and their opponents in Oregon--during the Share-A-Home program that brought thousands of street people into Rajneeshpuram in September 1984--Sheela, even while denying that the Rajneeshees were scheming to take over Wasco County as they previously had taken over Antelope, shouted at reporters: “Wasco County is so f-----g bigoted it deserves to be taken over.”

Despite the ever-escalating belligerence of the Rajneeshees, and despite growing evidence of Rajneesh willingness to flaunt if not defy federal and state statutes, most segments of the press and authorities at all levels of government were slow to react. Until September 1985, when Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh himself brought to light much of the criminal wrongdoing associated with the commune (absolving himself of all responsibility and blaming it entirely on Sheela, who had just fled to Europe), the only serious and direct action taken against the operations of the commune by any government agency was the lawsuit filed in 1983 by the Oregon Attorney General’s Office against Rajneeshpuram for violation of separation of church and state and the successful effort of Oregon Secretary of State Norman Paulus to the halt the voter registration of street people at the ranch during the Share-A-Home program.

Media representatives—like much of the Oregon intellectual community in general—were in many cases actually sympathetic toward the Rajneesh enterprise, viewing it as both an exercise of the First Amendment right of free exercise of religion and as a noble attempt to fulfill certain mutually shared ideals of community from the 1960s. In December 1982, when the Immigration and Naturalization Service denied Rajneesh the status of religious teacher (later revised), leading KGW-TV commentator and former Oregonian columnist Floyd McKay, in a commentary that began “Merry Christmas to the Bhagwan—Sorry, but there’s no room at the inn,” called the ruling “a charade” that “supports the idea that there are few things more ridiculous than bureaucrats deciding spiritual questions.” He also complained that “there is no place in America for the acknowledged spiritual leader of a quarter-million peaceful people” (although Rajneesh claimed a worldwide following of 250,000 to 300,000, the actual number of committed disciples was 10,000 or less) and declared that “beyond the heavy-handed treatment of the people of Antelope . . . the Bhagwan and his followers have done no harm to this region.” When Attorney General David Frohnmayer filed his church-and-state suit the following year, he was taken to task by the Oregonian editorial page (which would continue to take the Rajneeshees’ side almost until the very end) for picking on a “religious minority.” It was not until the summer of 1985—a scant few months before the whole Rajneesh saga in Oregon would abruptly end, and a full four years after it began—that the Oregonian finally produced an investigative series about the group. Even then the series completely failed even to mention the main event: the Rajneeshees’ attempt, in the fall of 1984, to influence the results of the elections to the Wasco County Court through a scheme involving the importation of street people into Rajneeshpuram as potential voters, the poisoning of two of the three county commissioners while they were on a visit to the ranch, and the food poisoning of several hundred restaurant patrons in The Dalles. It also would overlook the episode’s main import: the grave threat to public safety posed by the Rajneesh Medical Corporation.

Even at the end, when Rajneesh was back at his commune in Pune (Poona), Inida, and Sheela was in jail, aspects such as the involvement of Rajneeshees in international drug running, the sexual abuse of children at Rajneeshpuram during its heyday, and the possibility that the director of the Rajneesh Medical Corporation had been trying to develop a live AIDS virus for use against dissidents within the commune and the public remained largely unexplored by the press or the government. “It was,” an official of the U.S. Custom’s Service in Portland was to say in retrospect to this writer, “the biggest criminal conspiracy in the history of the state, and no one did a damned thing about it.”

Win McCormack

|

The Rajneesh Chronicles:

The True Story of the Cult That Sought to Kill Two Thirds of the Human Race

The Rajneesh Chronicles:

The True Story of the Cult That Sought to Kill Two Thirds of the Human Race

Comment on it

Comment on it